Memoirs 1936–2011

Chapter 16 1965 Last term at Art School and Return to New York

A visit from Richard Feigen.

Back to New York.

‘4 Young Artists’ Exhibition.

Two weeks later, Richard Feigen appeared in Fournier Street in a large black chauffeur driven limousine. He seemed as determined to transmit the image of an affluent and powerful art dealer as I was to receive it. Articulate, energetic, square-jawed and wearing heavy horn-rimmed spectacles, he looked like Clark Kent, Superman’s alter ego. His arrival was so rumbustious and frantic it did indeed seem that he might have crashed through the wall of the studio, rather than ascended the stairs. He exuded a bombastic confidence which was entirely strange to me; he projected an air of competent success which I had not come across before, and which I was far too naive to recognise as a performance. I could only conclude that he was a denizen of some alien and incomprehensible Utopia, and that his life was quite different from mine. But he enthused over my paintings which stood piled against the walls of the old room which had served so long as my studio, and it appeared that they had some value in his eyes, a value that could be realised in the world which he inhabited.

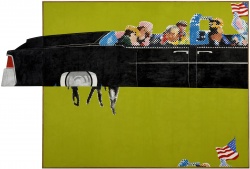

It was quickly agreed that almost my entire body of work should be shipped immediately to his gallery in New York, with the intention of mounting an exhibition of them that autumn after I had finished my time at St Martin’s. The only paintings he did not take were ‘Anna Karina’, which he said was too tall for his gallery, and ‘Lincoln Convertible’, my painting of the Kennedy assassination, which he said would offend and depress people. This was my first experience of the editorial pressure which dealers invariably attempt to apply to the artists with whom they are working. Feigen’s instinctive reaction to the Kennedy painting was wrong; compared to, for instance, Warhol’s ‘Electric Chair’ or ‘Car Accident’ series, it is positively decorous. His censorship of the work led to my placing it in storage on my departure for New York, where it remained for the next thirty years; it was eventually exhibited for the first time at the Barbican Art Gallery in London in 1993. It is based on the 8mm Zapruder film of the event, and it is recognised as being the only painting of the assassination of JFK painted at the time, which is, I think, really quite extraordinary, and strange indeed that no other artist cared to approach the subject.

However, I was very pleased with the results of our meeting. Feigen departed as he had arrived, swathed in gleaming black metal, his driver no doubt wondering what had brought his passenger to such a depressed and derelict part of the city.

I returned to my painting with a renewed vigour. Even a small amount of interest and encouragement from the outside acts as a spur, for most of an artist’s activity must be entirely self-motivated, and often seems similar to dropping a stone down a very deep well; it is ages before you hear the sound of the splash.

As my final student days were slowly consumed by the passage of those last few weeks, we began to make our arrangements for departure. Visas were no problem; the quota system whereby Europeans received favourable treatment was still operative, for even though it had been abolished by the Kennedy administration, the change in the law had not yet been put into effect.

Having parcelled out our responsibilities for the time being, Jenny and I were free to leave for New York as soon as term ended. This was both unwise and unnecessary because New York empties in the summer; everyone who can afford to, including virtually the entire art world, decamps to the beach or the countryside in order to avoid the boiling temperature and sweltering humidity of the city in high summer. We were unaware of this and in any case I could not wait to begin my new life.

Once more I belly flopped into New York without any clear idea of how I was going to survive. Richard Feigen had bought a couple of my paintings to show commitment and Robert Indiana had sold my ‘Navy Pilot’ to Dr Arthur Carr, a noted early collector of Pop art, who still owned it more than thirty years on. But the purchase prices were very low and the cash realised would not last very long.

In June, just before my arrival, Feigen had tested the waters by having a group exhibition of some of the artists he intended to represent. The New York Times review took the line that we were all too modish and clever for our own good, which in the climate of the time was hardly a criticism. I was described as ‘a first class Pop man, expertly using the new pointillism that breaks out everywhere like measles’. Feigen sold my painting ‘G Force’ from this exhibition. G Force shows a pilot losing consciousness in three progressive stages during early experiments in space research. It was painted on silvered canvas in one of my efforts to obtain a perfect metallic quality in my work, and was bought by Ronald Winston. He had just left Harvard and begun to work for his father, who was at the time probably the biggest and most successful diamond dealer in the world. He is immortalised by Marilyn Monroe in her breathless song ‘Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend’, when she murmurs “Talk to me, Harry Winston”. But the exhibition was the last event of the season. We could not expect anything else to happen until everyone came back from the beach and the countryside in the autumn.

Richard Feign had owned a gallery in his native Chicago for a few years. He had also established partnerships in New York and Los Angeles - in the former city, with David Herbert, he had the Feigen-Herbert Gallery and (rather confusingly) in the latter with Herbert Palmer, where the gallery was known as the Feigen-Palmer. Recently, he had dissolved his relationship with David Herbert, and the gallery in New York was now known as the Richard Feigen Gallery. At the same time, he had got rid of most of the artists chosen by Herbert and moved to New York in order to run the gallery himself. He was therefore at the beginning of his attempt to penetrate the New York gallery structure. Richard worshipped Leo Castelli and coveted his stable of artists. They were unavailable and immovable; Castelli and his sidekick, Ivan Karp, were doing very well by them all and they had no conceivable motive for switching to a novice dealer from Chicago. The system of comparatively new galleries which had emerged and which were beginning to deal seriously in the new art - that is, loosely speaking, Pop art - had to accept him as an equal if he was to succeed and he needed a strategy which would facilitate this. He therefore chose the so far untapped but fertile field of young British artists. It was an inspired move; the quality of the work was good, it was fundamentally different from its American equivalent and the very term ‘Pop Art’ had originated in London.

British stock in the US was at this time very high. We were popular there then. This is why he had contacted me and, at the same time, Allen Jones, Peter Phillips, Bridget Riley and Philip King. He had some Americans in his stable too - Chuck Hinman and John Willenbecher, for example - and an amiable and articulate Chilean named Enrique Castro-Cid. But his main interest was in British art. I was to be the first of these artists to exhibit in the campaign to win attention; my exhibition was to open on September 20th.

The gallery was at 24 East 81st Street in an ornate stone-fronted building with decorative columns at either side of the ornate entrance steps. It had two clear white exhibition spaces. Virtually all the galleries at that time were concentrated either on the Upper East Side or along 57th Street in midtown. None had as yet opened downtown in the area which was later to be known as Soho, or on the Lower East Side or Chelsea. Those which had survived in Greenwich Village since its Bohemian heyday in the 1940s were no longer taken seriously. Feigen had the advantage of being on the route which an interested person would take when travelling around the galleries of the Upper East Side; in particular, he was close to Leo Castelli, whose gallery was on East 74th Street. Because there was so much to be done, the Richard Feigen gallery remained open all summer.

The person in the gallery with whom I had most in common and who became my closest friend was Michael Findlay. He was a palely beautiful youth who, overwhelmed by seeing John Cassavetes’ film ‘Shadows’, had left London and come to New York in order to become an actor. His employment at the Feigen Gallery was intended to be temporary, a means of survival while he pursued this ambition. Richard Feigen gave him the grand title of ‘Director of Exhibitions’. His duties included crating and uncrating paintings, handling and hanging, labelling and lighting, and sweeping the floor. Although he found himself in the art world by accident, his personality and education suited him to the work; he quickly became an important and active member of the gallery staff while at the same time pursuing with enthusiasm the increasingly louche possibilities of life in the city. His intention of becoming an actor was gradually abandoned as he became more expert and influential in the art world of New York. Slowly, he became a key member part of the sales team, his British politesse and education contrasting favourably with Richard’s brash and forceful approach. People who felt uncomfortable when confronted with Richard’s wild staring eyes and flaring nostrils would speak instead to Michael; and thus the range of possible clients was increased. A similar but more extreme system operated at the Castelli gallery, where Leo, with his smooth and sibilant and European approach, dealt subtly with the customers while his assistant, Ivan Karp, loud-jacketed, cigar chomping, with piercing popping eyes, fast talk and bristly red hair, would startle them by shouting out suddenly “I sure hope ya brought ya check book with ya!”.

For the first week or so, Jenny and I stayed in a small hotel at the junction of Macdougal and Bleecker Streets in Greenwich Village. I had taken my unorthodox print-making a little further down the impractical road which had begun with the Oxford art school Xerox machine. Now I was making Skydiver images using stencils which I cut myself and through which I sprayed aerosol auto lacquer onto highly absorbent Japanese paper. The fact that I was staying in sweltering summer in a small hotel room without air conditioning and in the middle of the city failed to deter me from my work - and it is to Jenny’s credit that she did not complain at all when she found herself enveloped in highly inflammable and toxic fumes in this claustrophobic environment. Of course I kept the window open but the heavy cloud of vapour stubbornly refused to vacate our room and sat there sullenly in spite of all my wafting with cardboard and waving of the doors to and fro. Yet still I made just one more print day after day, when we were not out inspecting the city which was to become our new home.

One evening in a bar close to the hotel, I met a young black man who had recently arrived in New York from rural Georgia. Talking on almost any subject, as one does with a casual acquaintance, we somehow found ourselves discussing fishing. He described to me how he used to fish in shallow streams with a home-made trident, spearing with it the small fish which lurk beneath the rocks and flash quickly from pool to pool. He said “I used to stand up on them rocks with my fork jes’ like Possydon, baby!” What culture is this, I thought, where a poor boy fishing in a Georgia stream can picture himself as a sea god? How was he so familiar with classical mythology - and, more importantly, how did he have the self confidence to visualise himself in such a grand manner? Few children in Britain knew of Poseidon; none would be likely to identify with him. I thought of my own persistent but unsuccessful pursuit of gudgeon in the stream at the bottom of the garden of our rented house in Dorset (an endless summer of cold wet feet which ended in my contracting a very painful rheumatic fever) and realised that understanding this difference between our cultures was one of the keys for unlocking the mystery of this new country and its noisy boastful self-confidence and simple, positive approach to life.

In London I had met two young Americans, husband and wife, who were studying acting with a legendary teacher. The technique he taught was a spin-off from the Method school, for they were always talking about ‘expressing’ and being ‘bound’. I was singled out especially as an example of this latter, dismal characteristic. Michael Abrams (whose father Harry had established the great art book publishing firm) and his wife, Susan, nevertheless became good friends of ours and, indeed, Michael had supplied the American voices for the soundtrack of my ICA performance in London. Before we left for New York, they gave us introductions to their two sets of parents and warned them that we were coming. Soon after our arrival we met these kind people. Susan’s parents lived in the Beresford, an enormous and ornate late nineteenth century apartment block on Central Park West and 81st Street. It is one of those extravagant buildings of which there are many examples on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. They were erected in the 1880s and 1890s before the subway was built over on the East Side, enabling its residents to travel to and from Wall Street more easily, and this outweighed the attractions of the splendid views over the Hudson River to the Palisades which the West Side enjoys and which contrast so favourably with the flat islands of the broken land to the east.

Susan’s parents offered us a room in their apartment, saying that we could stay with them until we found a place of our own. This was extraordinarily kind and helpful of them but the thought of living with comparative strangers in their own home did not accord with my idea of the type of life I wished to live, and the embarrassment of feeling both obligated and uncertain about the possibility of coming and going at will dissuaded me from accepting their offer. They then proposed, somewhat doubtfully, that we should have their unused maid’s room in the basement of the building. Bleak and uncomfortable though this was, it suited me better than (what I perceived to be) the stifling comfort of their large and well-appointed apartment. Jenny concurred, though I do not know if she really preferred this tiny concrete walled cell with its single iron bedstead, no window and small dripping sink, deep in the bowels of the building, festooned with exposed plumbing pipes and surrounded by fenced-in storage areas belonging to the many apartments on the floors above us. But to me it had the inestimable advantage that it was completely uncompromising. I wanted to start from the beginning, and this functional cupboard like space offered no threat to the purity of my approach. Hot, airless, uncomfortable, with nowhere to sit and barely room to stand in, it had a tough and brutal quality which helped me to position myself where I wanted to be: on the outside, uncompromised, remote and independent. I wanted to give no hostages.

The Abrams were equally hospitable. They immediately took us out to dinner and Harry, acting on his son Michael’s advice, bought the first Skydiver painting that I had made at Indiana’s loft on Coenties Slip. Harry was a short powerful man with an aggressively pleasant manner and the disconcerting habit of, when you were speaking, suddenly saying “Just a minute, just a minute, I must interrupt,” and then reaching forward and carefully removing some small and, I suspect, entirely imaginary piece of detritus from your collar or shoulder.

It had the effect of throwing you completely off balance and returned the initiative to Harry, especially if you happened to be in the middle of answering a question put by him. It was deeply irritating but I don’t think that Harry cared about that because it kept him on top of the situation.

Nevertheless, he was kind to us and indeed lent us a car for a few weeks, which enabled us to get out of the city into upstate New York and to Long Island.

The basement maid’s room was too small to work in even for me. In any case, we spent most of our time looking for somewhere to rent. I did not yet kniow how to set about finding large commercial spaces, so we eventually we found a sixth-floor walk up tenement apartment on Sixth Avenue just below Houston Street. It was domestic enough to accommodate our daughter too. It was what is known as a ‘railroad’ apartment - that is, the rooms led from one to another in sequence, so that to get to the farthest you had to walk through the others much as you might walk through a line of railway carriages. In grander edifices, this arrangement is known as ‘rooms in enfilade’ but there was nothing reminiscent of the 18th century about 188 6th Avenue.

It had two bedrooms, a living room, kitchen and lavatory. The bathtub was in the kitchen under a piece of wood which served as a table. It had been built in the 1890s according to the new health codes, which demanded a certain minimum amount of daylight and air circulation in all buildings, qualities difficult to achieve in the typical New York building plot, which is very narrow and very deep. Twenty five feet was the standard frontage for a single building once the grid system of streets had been laid out in 1811, and the depth of each plot was one hundred feet. For buildings other than those on corner sites the difficulties are self-evident. The tenement in which I was now living occupied several such plots. There were four apartments on each floor. These were arranged around two narrow light wells which stretched from ground level to the roof six stories above. These light wells were no-man’s land - a place where no-one could go and where window frames were never painted, brickwork never pointed, festooned only with odd redundant wires and aerials, vestigial clothes lines and pulleys, and laced with snatched of conversation and occasional yells floating through the open windows on each floor.

On our floor lived a slack-bodied woman who never seemed to leave her apartment, only appearing on the landing several times a day to screech loudly for her teenage daughter to come upstairs from her habitual seat on the front steps of the building. “Ma-a-ary Yanne! Ma-a-ary Yanne!” would echo down the stairs that were rather surprisingly made of steel and paved with marble in order that they should be fireproof. This was the result of another piece of hard-fought late nineteenth century legislation, as was the existence of the iron fire escapes cascading down the back and front of the building, rendering all the apartments extremely vulnerable to intrusion but providing both some hope of escape in an emergency and an open-air perch in hot weather.

In the apartment opposite ours lived a young and pretty couple from the Mid-West. They were aspiring actors already doomed by the lack of any particular distinguishing quality and by the tiny baby for whom the wife had already surrendered all of her ambitions, though the husband still trudged doggedly from audition to audition, holding body, soul and hope together with whatever work he could find.

Meanwhile, in London the Arts Council had organised a touring exhibition which had been selected by Roland Penrose from the previous year’s Young Contemporaries. It was to open at the ICA in October, so when Jenny went back to London to collect our daughter, Yseult, and to move out of Fournier Street, she also arranged for a few new works I had left in London to be delivered to the gallery. The exhibition was entitled ‘Four Young Painters’; the others were Douglas Binder, David Hall and Roger Westwood. The poster for the exhibition was printed on silver card and showed a young girl with short hair wearing sunglasses, a tee shirt and jeans, leaning on the bonnet of a sports car of indeterminate make. She looked posed and uncomfortable, as though forced inwillingly into the unfamiliar mould of the photographer’s fantasy. With its naive yearning for an imperfectly defined glamour and a dangerous sophistication, the poster encapsulates the mood of the time: a mood impatient for release from dull reality but uncertain how to achieve it.

Meanwhile, in New York I set about making the apartment more congenial, painting the walls and ceiling and, in the two bedrooms, making versions of the wooden platform beds which were to become a feature of all my New York accommodation - simple structures with storage space beneath them and a six inch thick slab of foam rubber on top which served as a mattress. They were not very comfortable but they were cheap to make.

Various parts of the apartment and some fittings were definitely sub-standard but when I complained to the landlord about them, he growled “Don’t get legal with me, Laing. If you don’t like it as it is you can get out”. I chose to stay, at least for the time being.

It was hot on the top floor of that building. The sun baked the apartment through the tar-patched roof, which sloped slightly towards the rear of the building and was crested by the usual ornate neo-classical corbels and mouldings made of pressed rusty metal. Going up on the roof via the fire escape in the summer evenings is an accepted city practice and has, for those who grew up there, some romantic connotations, representing a freedom from the claustrophobia of the family apartment and a space to indulge in activities impossible elsewhere in the building. Tony Curtis, for instance, described in his autobiography how he used to drop water-filled condoms on the heads of the members of the fascist Deutsche Bund as they marched along the streets of Yorkville on the Upper East Side. But the sad material condition of the environment and the lack of guardrails or parapets of a useful height did not encourage me to spend much time up on ours even in the hottest weather. The surrounding roofscape crowded with plumbing afterthoughts and elevator housings, the visual cacophony of old and new building and the ubiquitous stilted wooden water tanks which, with their conical roofs, look like the dwellings of a primitive people, is a complete surprise to the newcomer. The contrast between dereliction, shiny new structures and the gothic fantasies of the tops of the older buildings presents a surreal architectural vision. On the rare occasions when everything is swathed in mist and fog, and only the tops of the buildings are visible looming above it, you can imagine yourself in a vast dream city.

As soon as I had cleaned up and organised the apartment, I set up my studio in the long narrow sitting room which was lit by two windows at the far end. They looked out over Thomson Street; below was a playground with a basket ball court, surrounded by a chain link fence of the type common in America but which I had seen only in the stage version of West Side Story. The Jets had climbed up and over it with remarkable agility and the final disastrous fight had taken place in just such a playground as the one now beneath my windows. The musical had given such things a romantic air; the denizens of this real playground, mostly local Italian youths shouting and cursing as they argued and played - or drinking and smoking as they harmonised ‘The Duke of Earl’ in the warm nights - assumed in my eyes a far greater glamour than they deserved. West Side Story had glamourised them and by placing its grand theme amongst the poor and ill-educated, it echoed John Gay’s ‘Beggar’s Opera’ and complied with the philosophies of Genet and Camus. I believed that I would, if I knew them, find these people more interesting and authentic than those of the bourgeois society I had just quitted. I sustained this delusion for a long time in spite of all empirical evidence to the contrary.

I equipped myself with paint, turpentine, brushes and canvas from the New York Central Art Supplies on Third Avenue, to which I had been introduced by Bob Indiana. This was one of the first stores to sell a comprehensive range of artists’ materials in quantity and comparatively cheaply, to which I had been introduced by Robert Indiana. Wood for the new heavy stretchers which I had learned to appreciate when I was working on Coenties Slip came from Broadway Lumber nearby. Soon I was hard at work, developing the Skydiver and Dragster themes I had begun the year before. The days passed happily as I painted in peace, pausing only for frequent cups of tea, cigarettes and elementary meals. My exhibition at the Feigen Gallery was only a few weeks away and I needed to have as much work as possible ready for it.