Memoirs 1936–2011

Chapter 13 1963 First Visit to New York

Gerald visits New York for the first time and meets Robert Indiana, Andy Warhol, Jim Rosenquist and Roy Lichtenstein.

He works for Robert Indiana in his Coenties Slip studio.

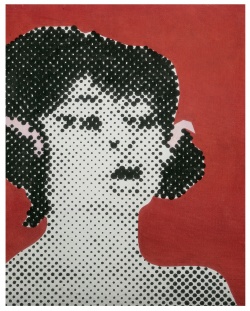

He paints Jean Harlow and the first of the Starlet, Dragsters and Astronauts series.

On my return to St Martin’s, I found that one of the students was selling £50 return tickets for a two month visit to New York during the summer. At the same time, an uncle (quite uncharacteristically and for no particular reason) sent me fifty pounds. The conjunction of the unexpected windfall and the cheap ticket seemed reason enough to take advantage of the offer. I had no particular desire to go to America, but at the same time I was concerned about the future and I knew that I should leave no possibility unexplored. I did not expect to find any answers to my problems by going to New York but at least I would see it at first hand, and my opinion of it would be based on my own direct experience. The student who was the agent for the airline tickets had himself been there the previous year but he could tell me little about it except that Central Park was dangerous and that you should not say thank you to the token sellers in the subway booths. I knew that I would have to earn enough money to live on while I was there because there would be no spare cash at all for me to take with me. He assured me that it was comparatively easy to get casual work, perhaps in a bar or restaurant; with that assurance I made my decision to go.

Fortunately, I remembered that Richard Smith, who was teaching part time at St Martin’s had recently returned from a two-year Harkness Fellowship in New York. His paintings were unlike any others I had seen. They were based on the devices and inventions of advertising and display and they were accomplished and confident and superbly painted. ‘Smith’ s genius’, wrote David Mellor in 1991, ‘was to find the lyrical, transcendent element in this profane illumination’6.

New York had affected him very deeply. He had arrived there in 1959, at a time when the art world was still very small, so that all the painters knew each other and those few dealers who would actually exhibit contemporary art needed to be totally committed to it. They had little thought of profit, since sales were few and prices were low. At the same time, their commitment, when it did exist, was very firm and gave them a strong sense of purpose. Under the American aegis, the approach to painting had become analytical; it was as though, for the first time, paint itself had become a subject in its own right. Richard was sympathetic to this approach and it contributed to his insight and encouraged him. He had quickly become a part of the new art world and he benefited from the immediate interest in his work which was expressed by his new friends. He had his first one-man exhibition at the now legendary Green Gallery in 1961. This gallery, which was founded and run by Richard Bellamy until it closed in 1965, was the most important forum for painters who emerged in the early 1960s, predating by several years the far better known Castelli Gallery.

Many artists were given their first exhibition by Richard Bellamy, among them Rosenquist, Wesselman, Oldenburg, Judd, Morris and Segal. Bellamy possessed the unerring judgement and discernment of one who had his finger on the pulse of his time. In his gallery, the foundations of the monolithic and juggernaut art phenomenon of the 1960s were put in place.

Very little of this had been seen or heard of in Europe at that time. Of course, we knew about Jackson Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists, but they seemed quite remote and not particularly relevant to the European experience. National boundaries and national cultural identities were so far intact -and abstract expressionism seemed to be a local American phenomenon much as Existentialism seemed to belong to Paris. Both appeared to wilt and die if they were transplanted. What was soon to become quite clearly defined as American cultural imperialism was still gestating in the warm and fecund loam of its native hearth; it had not yet been subjected to the remorseless promotional techniques which were eventually to ensure its total ascendancy, when it became ‘the idiom of personal emancipation, and it was useless to attempt to explain that the acolytes of this cultural misadventure had simply made themselves captive to a fashion as lethal to their real artistic independence…. as the local conventions they rejected’7.

But so far my own exposure to all this had been confined to a lecture by Ad Reinhardt at the Institute of Contemporary Art, at which he recited some of his long lists of aphorisms. These seemed to depend on puns of the type indulged in at meal times by the most boring and pedantic of schoolmasters. He failed to explain why he painted his almost totally black paintings. All we managed to ascertain was the fact that even though the vestige of imagery which remained in them assumed the form of a cross, this definitely had no Christian or religious significance. In desperation, one student asked him what he did when he first entered his studio in the morning and he replied, “I sweep up”.

The lecture was a failure because he did not succeed in convincing us that his preoccupations were either significant or interesting. At the same time, it was memorable for its puzzling lack of content or purpose. We had not yet learnt how to suspend our disbelief nor had we discovered the new importance of the merely memorable.

The Pop Art movement had not been defined in American and its individual practitioners there were virtually unknown in Britain. Indeed, their work had scarcely been seen in America. I certainly had not heard of the four artists to whom Richard gave me introductions and I had no idea that within a year or two they would be acknowledged as the leaders of the American Pop Art movement. They were Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Indiana and James Rosenquist.

Before I left for my two month absence I parked my Austin Seven opposite the front door of No. 12 Fournier Street, where it stood unlocked and unmolested all summer long. I ran a chicken wire fence around the railings of the flat part of the roof of the house, for I had a reoccurring image of my daughter Yseult (who was then aged two) rolling down the slates, bouncing off the gutter just beyond my reach, and falling into the street below. This did in fact not occur, thank God, and was probably a manifestation of my guilt at leaving my young family for such a long time. Somehow we scraped together enough money for Jenifer to live on during my absence. I took only a few pounds with me.

An American artist in London had very kindly arranged that I should stay with a friend of his called Al Fried whilst I was in New York. So although I had very little money with me when I arrived, I did at least have somewhere to stay and, buoyed up with the optimism of youth, I felt sure that I could get a job somewhere in order to support myself. What else I might achieve I had no idea.

Al Fried lived in a dark book-lined apartment in a brownstone house on East Ninth Street. It was accommodation very typical of the type inhabited by New York intellectuals at that time, with the curtains seldom drawn open, the walls stripped to bare brick and bookshelves made of planks supported on further bricks or on concrete blocks. The remainder of the furnishings consisted of odd items accumulated from second hand shops and dumps; shabby, dusty and comfortable. Little or no attention was paid to the appearance of things the demarcation lines between the literary and the plastic arts were (and remain) pretty firmly drawn.

Al was a political writer who looked a lot like Danny Kaye and who introduced me to various basic left wing ideas which had never occurred to me before, but which later became a sort of common currency, giving us the world view which differed so much from that which came before. They contributed greatly to the sense of malaise and guilt which, in their turn contributed significantly to the political and social upheavals which were about to begin.

In 1963, New York was still a very conservative place. People dressed and behaved in a uniform and circumscribed manner, and even the slightest expression of individuality might be criticised vociferously. Americans were confident that their values and their way of life were the best, and reacted quickly to any perceived threat to them, however mild. They had recently spent years contemplating the investigations of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which had pilloried unmercifully some of their most prominent and talented citizens. The fact that this had been in response to a very real threat from the Eastern bloc and its ideological anathema lent considerable weight and authority to any attempt to maintain the status quo intact and inviolate. The smallest aberration from the accepted norm could cause concern and create a reaction. Even my carefully trimmed beard was singled out for public criticism, and several times as I walked the streets a voice would callout loudly and rudely: “Hey, Mac, ya lost your razor?” Prejudice which now would be considered intolerable as well as illegal existed without comment. In one Third Avenue bar, an enormous painted plywood axe hung behind the cash register with the words ‘FAG SWATTER’ painted in large letters on a board below it. I note these facts to point up the volatile nature of America’s Utopian quest.

Richard Smith had chosen my four contacts because they seemed to him most likely to be in sympathy with my work. They were all painters who depicted images clearly and for whom the figurative content of their paintings had supreme importance. None of them was related either backwards towards abstract expressionism or forwards towards colour field painting. They were not sensual painters, indulging in the quality of the material for its own sake; they tended rather to use it simply as a means to an end, that of creating the images. Although they had this in common, they were otherwise very different.

I telephoned each in turn, and visited them over a period of two or three days. I thus had a rapid tour of an important section of the New York art world, a world about which at that time I knew nothing at all. I was not prepared for the level of professional commitment that I was to find, a commitment made possible by the unshaken belief in the importance and relevance of art. In Britain, we were almost forced into an amateur mould, partly because amateurism was somehow considered to be more respectable than professionalism and partly because it was almost impossible to conceive of a way in which our society would find contemporary painting and sculpture to be significant. No such inhibitions bothered the Americans: they took themselves quite seriously and were convinced of the significance of what they were doing. The idea of the alienated artist, the misunderstood outsider, the lone prophet working forgotten in his garret (a myth which nurtured the European and ameliorated the pain of neglect was of no interest to them. They had a product, they stood by it and they were very happy to tell you about it. The marketing methods which have made America great had not yet been thoroughly applied to the art world, but the style and expectations of the market place were already there, poised to propagate the products of the studios. In this world there is no room for diffidence.

I met Jim Rosenquist first. He is a Scandinavian from the Middle West. Fair skinned and blond haired, stocky and strongly built, he gave the impression that he could as easily be at home on a tractor in some vast grain prairie, with only the giant silos beside the railroad punctuating the horizon behind him. His studio was a big untidy loft - a hundred foot long room in a steel-framed Victorian industrial building with a planked floor and a ceiling made of embossed sheet metal supported by quite ornate cast iron columns. Windows stretched all down one side and across the end of the room. It was as different as could be from the typical London studio, which more often than not was the front room of a terrace house in Notting Hill.

Jim easily filled this huge space; vast canvases were propped here and there against the walls, a steel table held a clutter of drawing paper, correspondence, bills and paints and the floor was almost completely covered in a sea of old coffee cans which he used as paint pots.

Jim’s technique owes everything to the advertising billboards which he used to paint for a living. These often exhibit an astonishing degree of skill. Most of them were then actually painted on site and in all weathers. There is always a predetermined gridded plan or drawing, but nevertheless the scale of the work requires real vision. And who is to say that painted foam and a misty chill of condensed moisture sliding down the side of a glass of Heineken forty feet high is worth less artistically than any other still life?

Once I was walking along Canal Street when a paint-covered man backed into me. Oblivious of my presence, he was peering up at his latest creation, a particularly fine rendering of bubbles and gassy liquid in a cold glass high above the street and a hundred yards away. Sign painters must be able to stand back from their work just like other artists and I congratulated him on his achievement.

Jim had been employed by the strangely named sign making firm of Artkraft Strauss, for whom my beer glass painter also worked. Jim used the techniques of sign painting - in other words, a straightforward, skilful and economical system of realistic depiction. The only difference was in his choice of subject matter and the juxtapositions he made between one image and another - incongruities which were intended to satirise and criticise American consumerism and militarism. Jim’s ideas and theories were essentially political; they were left wing, pacifist and anti materialist but tempered by the comfortable aura of the Mid-Western community from which he came. They were not raw, aggressive or threatening - nor surprising in the way that his paintings often were.

In the paintings, the contrast between a plate of spaghetti and a car door, or an airplane and a little girl under a hair dryer prompted more speculation than did Jim’s political theories - which was as it should be.

Success came to Roy Lichtenstein comparatively late in life. He was almost forty years old when he made his first cartoon-based painting and began regularly to exhibit the images which have made him famous. His neat small figure, thatch of lank hair and engaging smile gave him a permanent youthful charm so that he seemed always more boy than man. He pursued his career with a wise tenacity, keeping his work within quite narrow and specific boundaries designated by technique alone. The other artists I met all urged me particularly to visit him when I showed them photographs of my paintings of Anna Karina and Brigitte Bardot because of the apparent similarity between his approach and mine - in other words, because we both used dots to form the image. In fact, our techniques and, more importantly, our interests were quite divergent. He used Ben-day dots, silk-screened or stencilled onto the image as a tonal effect, while my hand-painted dots of different sizes were a method of describing volume and hence a system for drawing. In addition, there was no note of satire in my work; I was trying to make icons that were in the commemorative or laudatory tradition but which were executed in a new way. His images, like much of American art, often had satirical intent.

Over the years, Roy’s acidic edge blunted somewhat and his later work became either nostalgic, as though harking back to a better past, or mannerist, in that the chief interest might be in the brilliance with which he used his technical vocabulary to paint first this and then that unlikely subject. His innate and kindly gentle humour became increasingly evident in his later work.

For me, his most important painting is ‘Peace Through Chemistry’. It is a devastating comment on our notion of progress and the unforeseen effects it produces and as such is an important political document. At the same time, amongst the drug-addled young of the mid-sixties, it gained an extra significance which was not lost on those who saw lifr through a mist of marijuana or a crumbling psychedelic landscape. Peace through chemistry indeed!

His War Story paintings, such as ‘OK Hotshot, I’m Pouring’ come from sources imbued with innocence, similar to those which I remember from my own youth. The British equivalent, for instance, would be the boy’s comic ‘Champion’, which featured an indomitable craggy-jawed hero called Rock-Fist Rogan of the RAF. Whenever he was shot down in his Spitfire, he would simply punch his way to freedom, past the apparently impotent sub-machine guns of crowds of German soldiers. My approach to my own heroic subject matter at that time was similarly uncritical and adulatory and if there are coincidences between my work of the early sixties and Roy’s, then they are to be found in the joyful approach to subject matter and not in the use of dots.

Andy Warhol, waxen complexioned and still with a thick mass of his own lank and greying hair, his complexion devastated by acne scars and his delivery wan and apparently indecisive, had not yet moved into the building on Union Square which was later to become known as the Factory. He lived with his mother in the house on Lexington Avenue which he had bought while he was still working in advertising. I met him at his studio, which was an old fire station on 87th Street. It had recently been bought at public auction and was semi-derelict. There was no water, telephone or electricity in the building and very little natural light. Andy was able to rent it cheaply while its new owner was making up his mind what to do with it. The advantage it had for Andy was that it was only a short distance from his house.

The studio had a necessarily temporary and accidental feel to it; a few pieces of ill-assorted furniture stood about on the cracked concrete floor and the walls were crisped with peeling paint. There was little sign of activity and none of the weird conviviality which was to come later as Andy assembled his group of helpers and hangers on. Only Gerard Malanga worked with him at that time. Gerard was short and thickset with black wavy, greasy hair and a roughly chiselled face. He wore all-black clothing - a black tee shirt, black jeans and a black leather jacket. He looked like rough trade from Brooklyn, as well as being a poet and a graduate of Wagner College on Staten Island. His hard - ass appearance was an identity which suited him as well or better than any other I could imagine.

I cannot remember having had any significant conversation with Andy when I met him, or indeed at any other time during the years which followed. It is very likely that there wasn’t any. He had not at that time perfected his bland non-sequiturs, such as “I like boring things” or “Machine have less problems. I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?” but even so I do not think that he ever engaged in a dialogue. His technique was that of the sophisticated interrogator, the showman or the confessor; he laid down a neutral ground onto which, if you engaged with him, you would be forced to project your own inner thoughts and reveal yourself. How much he himself might contribute to these insights is debatable. He was more a mirror than a creative force.

That evening he suggested that I might like to go with Malanga and another youth to a lecture on film which was to be given by the avant-garde film maker, Willard Maas, and his wife, Maria Mencken, at Wagner College. We went by car and on the ferry to Staten Island. My two companions smoked marijuana. This was the first time I had seen it used and it took me a few moments to realise what was happening. They offered me some but I found the whole event too strange and disquieting and refused it. I mention this in order to illustrate the comparative innocence of us Brits at that time. We soon caught up.

I cannot remember anything of the lecture, but I can remember very clearly that, at the end of it, Malanga the other man and I were asked by Professor Maas to help to replace the chairs which had been used in the hall. Much to my surprise, Malanga gave a Fascist salute and screamed “No fucking chance, you Fascist Hitler bastard”. This seemed to me to be an over-reaction to a perfectly reasonable request. Possibly there was some old enmity between Malanga and Maas, who had taught him until recently. Certainly, it was my first experience of that anarchic, challenging and above all self righteous bad behaviour which became an accepted mode later in the sixties.

As one of Warhol’s first associates, Malanga was at first an active and vigorous member of the Warhol community, but later there was trouble. Warhol always made a big thing of the fact that almost anyone who happened to be in the Factory could silkscreen one of his ‘paintings’ which could then be ‘signed’ with a rubber stamp signature which read ‘Andy Warhol’. Gerard Malanga called his bluff when he decamped to Italy with both the silk-screens for making small square flower paintings (at that time Warhol’s most popular image) and the rubber stamp signature. He started knocking out Warhols there and selling them. This produced outrage on the part of Andy, proving that there are always limits to freedom.

The artist who was most helpful to me and to whom I shall always be indebted was Robert Indiana. He asked me to work for him for the duration of my stay, and gave me a place to do my own painting as well. Dark haired, light bodied and square faced, with a long but retroussé nose and a sudden and disarming smile, he was a few years older than I. He came originally from Indiana, from whence he had taken his name. He was originally known as Robert Clark and his old friend, Ellsworth Kelly, with whom he at some point fell out, has always refused to call him anything other than Clark. In conversation, he has slow and rather convoluted delivery, peppered with quaint archaisms such as “it behoves us to do this” and many other of the conversational mannerisms of the Middle West, such as the habit of going “Uh-huh” in response to the words “thank you”. At that time, he occupied two floors of an old building on Coenties Slip at the southern end of Manhattan. This was an area favoured by artists long before Soho became fashionable; in the immediate neighbourhood lived Robert Rauschenburg, Agnes Martin (who obliged all visitors to her loft to remove their shoes in order not to sully her white-painted floors), Jack Youngerman and his wife, the French actress Delphine Seyrig, (who had just made the film ‘Last Year in Marienbad’) and James Rosenquist.

Coenties Slip has now been turned into a windswept plaza surrounded by towering office blocks but at that time it was still discernable as a slipway, though the inlet in which the ships used to float had been filled in and cultivated as a planted area known a Jeanette Park. Around it clustered the old red-brick mercantile and chandlery buildings which served the needs of the sailing traders. Four or five storeys high, each of them were surrounded by the elaborate cast-iron cornice typical of the nineteenth century. The facades were punctuated by sash windows with dark coloured woodwork. Inside, the floors were open from the front to the rear of the building and the embossed pressed tin ceilings were supported by rows of wooden columns, often with charming neo-classical detail. The ground floors were given over to humble retail and commercial activity; the upper floors used now for storage or standing empty. It was in one of these buildings that Robert Indiana lived, occupying the third and top floors. The floor below him was occupied and there was a noisy Puerto Rican bar at ground level. Across Jeanette Park was the Seaman’s Lighthouse Mission, a charity organisation where we could get lunch each day very cheaply.

The day after I met Bob I started working for him. To some extent the timing had been fortuitous; shortly before my arrival his long term relationship with the dress designer, John Kloss, had ended and Kloss had moved out.

John Kloss continued to visit Indiana occasionally and commissioned me to make a portrait of Jean Harlow. This I did, and the experience was useful because I had not been commissioned to make a large painting before and it forced me to tackle problems that I would not otherwise have experienced. John gave me a copy of the famous photograph of Harlow in a negligee, sitting cross-legged in a large armchair. I used a shaped canvas -one of the first I made -to show the outline of the chair, and half tone dots for the swansdown of her negligee and for her exposed flesh. All the rest I did in flat colours, remembering the fashions from my mother’s 1930’s wardrobe -especially the shoes, of which she had a great number. When I was four, I took them all from her wardrobe, lined them up along the road outside our house and attempted to sell them. My first customer betrayed me and my ‘shoe shop’ was quickly dismantled.

Kloss paid me with some of his wonderful clothes for Jenny, ones which are now seen as classic sixties masterpieces. Later he sold the painting at Sotheby’s and it is now in a corporate collection in Washington DC. John Kloss himself committed suicide in 1987 at the age of 49.

Throughout that hot summer I worked for Robert Indiana. I had never before encountered such high temperatures and such humidity and I found it so uncomfortable and strange that it seemed as if I was living in a dream. There was no escape from it, except by loitering in the air-conditioned chill of a bank for as long as I dared.

I worked in these unfamiliar surroundings of strange architecture, strange temperatures, strange weather, strange smells and strange sounds - one of the strangest of which was the remorseless percussive slapping of the helicopters landing and taking off from the Downtown Heliport nearby. The heat, the clear skies and above all the strong light beating down day after day making sharp angular blue shadows were totally different from the aqueous tints of northern Europe. This is the light which caused the 19th century American neo-classical sculptor, William Wetmore Storey, to guess that America would produce a sculptural tradition to rival that of Greece - a dream which was indeed partially realised by such sculptors as Daniel Chester `French and Auguste St Gaudens, then snuffed out by the after effects of the Armoury Exhibition of 1913.

My principal job was to stretch canvas onto beautifully made heavy stretchers of a design which I had never before encountered. They were sturdy and could not warp like European ones always did. Their frame members were two inches deep, two inches wide and not adjustable. The canvas was stretched over them and secured at the back with a staple gun. This gave the sides of the painting a special prominence. At this time, frames were dispensed with and the colour carried around the sides of the painting as well, which tended to reinforce the work as an object rather than as a window into an illusion.

Robert Indiana’s work is neurotically precise and every stage in its preparation is exact and careful. His canvas had to be stretched absolutely evenly; the staples which held it were regularly spaced and lined up and the corners of the cloth folded hospital-fashion and flattened. My military training enabled me to understand and comply with these demands and I was able to work to the standard he demanded without resentment.

Bob also made sculpture from detritus and beams taken from the old warehouses that were being demolished nearby. My other employment, a most finicky one, was to chisel the ends of these beams so that when they were placed upright they would stand on their bases perfectly vertically without rocking at all. My days would be filled with one or other of these tasks: canvas stretching on the big table in the upper studio or chiselling the hard seasoned oak of the beams on the floor below, the sweat running into my eyes. After 5pm, with plenty of daylight left, I would move to the area at the back of the lower loft which had been designated as my personal workplace, and grapple with my own painting.

Robert Indiana is best known for his painting of the word LOVE which he made in the mid-sixties. It is probably the most plagiarised image from the period because he did not copyright it. It encapsulates the aspirations of that time. He made several versions of the painting. It has the four letters grouped in a block with the ‘0’ tilted at about 45 degrees, which Bob later announced as referring to an erectile male organ, a detail about which most people remain blissfully unaware.

Much of Bob’s inspiration is derived from the peremptory and enigmatic verbal exhortations of the American highway. These words, such as YIELD, EAT and GAS are a litany of function. Completely lacking in grace or circumspection, they have the brutal poetry of inevitability. Indiana took these words and added others, such as EAT HUG ERR DIE, or YIELD BROTHER, YIELD SISTER. In his ‘Numbers’ series, the numbers are depicted once and for all as though he were attempting to create the archetypes of proliferating symbols. Only the number 5, which he entitled ‘The Demuth Five’ is significantly embellished, deriving as it does from Charles Demuth’s painting which was itself inspired by a line from William Carlos Williams’ vision of a fire engine, ‘I Saw the Figure Five in Gold’.

In the lower studio on Coenties Slip stood the three big black and white canvases of his Manhattan Triptych, with their three quotations from Melville: ‘THIS IS YOUR INSULAR CITY; CITY OF THE MANHATTOES; CIRCUMAMBULATE THE CITY.’ Upstairs, there were his Brooklyn Bridge painting, with its obvious debt to Joseph Stella, and his Mother and Father diptych. The latter consists of two panels, the first with the inscription ‘A FATHER IS A FATHER’, showing his father wearing a Homburg hat, an overcoat and no trousers, standing with his hand on the door handle of a model T Ford sedan, the surrounding trees reflected in the plate glass of the windscreen. The second is a mirror image, with his mother on the other side of the car, wearing a red velvet opera cloak but with her ample breasts exposed and bears the inscription ‘A MOTHER IS A MOTHER’. Indiana claimed to have been conceived in the back sat of that Model T. He told me that later his errant father left, and every evening his mother would sit on the porch of their house, cradling a revolver in case he returned, in a tragic parody of the traditional courtship of the American suburbs.

Bob gave me enough money to survive and I was extremely grateful for it because I had not expected to find such congenial and relevant work, nor the opportunity to continue with my own painting. I lived very frugally and an on-the spot three dollar fine for jaywalking that I received on my way to the subway one evening represented a major setback.

I had little opportunity to go about the city in pursuit of pleasure; but I was so committed to my own work and so engrossed in the developments I was making in it that I spent every possible free moment painting in the lower studio, going down to Coenties Slip as early as I dared on my weekend days off, and staying there quite late at night. I seldom went out in the evenings, and returned to 9th Street only to sleep. Once or twice, Bob took me to parties uptown, which gave me my first experience of a modern high rise building (there were none in the UK at that time). The spacious marble entrance halls made me think of Rome, as did the other guests who came from what seemed to me then to be far-flung corners of the American empire, the distant states united by a common allegiance to the American dream. Civis Americanus sum.

There is no doubt that at this crucial time Robert Indiana had a very strong influence on my paintings. His method of working was extremely methodical. His canvases were, as have said, immaculate. He kept two cats (one of which was suspected of being a murderer, accused of having pushed its younger brother off a window ledge to the street below). Like all New York cats these animals were never permitted to go outside. They were fed from small tins of cat food, and Bob kept and washed all of these tins and used them to mix his lucid colours. This was very different from the amiable paint-spattered chaos of Rosenquist, or even more untidy workers whom I was to meet later. He never used a palette; colours were mixed individually and in a sufficient quantity, not scraped together with a dirty brush. He applied his paint on a carefully drawn canvas in five or six thin coats using chisel-ended squirrel hair brushes. This is what gives his paintings such a perfect appearance, and equally makes them so vulnerable to damage. Like most Pop art, Indiana’s paintings do not survive the inevitable degradation of time at all well. They must be kept in perfect condition.

Up to this point, I had not used colour at all in my paintings. I had been entirely engrossed in the obsessive depiction of the half-tone image, using only black paint on a white canvas. My first Coenties Slip painting, a portrait of Ursula Andress in a seaman’s cap on which I inscribed the words ‘COENTIES SLIP’ was carried out in this manner. Now Indiana’s techniques of colour application, so far from the stubby hog’s hair brushes and muddy palettes of art school, indicated to me a way in which I might introduce colour into my work. In common with many other artists of my generation, I looked to popular imagery as a source of inspiration, bare - knuckled reality being too organic, too gritty and indeed, too disappointing compared with the brightly coloured and perfectly finished future which we saw just ahead of us.

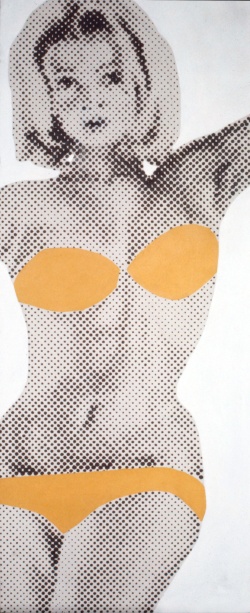

In Life magazine, I found an image which was to influence my work for the next few years. In an article on skydiving, then a comparatively new sport, along with the images of helmeted heroes leaping from aircraft, was a photograph of a red and white parachute collapsing as its passenger struck the ground, invisible behind some low scrub. This random array of red and white stripes, describing volume and pattern but infinitely variable, gave me a device whereby I could introduce abstract patterns to my paintings without losing the anchor of logic and reality without which I could not function. Just as I had referred to half-tone processes when painting in black and white, when I applied colour (which I did in a manner imitative of Bob’s technique) I did so as though it was applied by a commercial silk-screening process with a hard edge cut quite arbitrarily along the outline of the general shape it was covering. Sometimes the dots would overlay the colour along these edges, implying that the colour had been ‘printed’ first and the black dots added afterwards. It was a systematic process, almost digital in character. There was no modulation, or evidence of modulation, of colour or tone and no bringing the whole painting on together in the traditional way. This was a novel if deliberately gauche approach - although much earlier Stanley Spencer had worked in a similar, if much looser way, beginning his painting in one corner of the canvas and working across it steadily filling in the forms, with no or few apparent subsequent modulations of colour or tone. I intended it to be clear to the observer that my paintings were paintings of reproductions of reality and not of reality itself. They were a glorification of the consumer-directed and homogenised popular image, which in itself is a type of perfection; and they were the product of a repressed and fastidious mind, one disappointed by reality and irritated by the imperfections and awkwardness of everyday life, responding instead to a neat packaging of reality - an attitude which might seem les culpable when one remembers the time and the circumstances which produced it.

I searched Life Magazine and other similar sources for my subjects. Not only did I discover the parachute motif during this time on Coenties Slip, which led to my first Skydiver paintings, but I also painted the first dragster of a series with which I was to continue over the next two or three years. My first dragster painting was based on a photograph of Don ‘Big Daddy’ Garlits, who was the champion driver for many years. He came fro Tampa, Florida and named all of his cars ‘Swamp Rat’; the one shown in my 1963 photograph was Swamp Rat IV, though there were many more still to be built and raced. These cars, specialised to such a degree that their engines can only run for a few seconds, are designed solely for straight line acceleration over a quarter-mile course. The terminal speed record for this type of racing now stands at over 250 mph in under four seconds from a standing start. It is the most violent acceleration from a standstill known to man, and the cars are extraordinary objects, very long and slender with massive rear tyres to provide grip, and slender front wheels to provide the minimum amount of steering which is necessary to keep the car going in a straight line during its brief moment on the track. The driver sits just behind the rear axle and the engine, supercharged and running on exotic fuel mixture, is positioned just in front of it to place the maximum amount of weight over the driving wheels. As the wheels grip, vast roliing clouds of smoke from the burnt rubber of the tyres billow out behind the car, and when the engine is cut a few seconds later at the end of the strip, in the sudden silence a parachute is popped open, bringing the car safely to a standstill. The cars and the helmets of the drivers are painted in bright heraldic colours and the cryptic symbols of the sponsors. They race in pairs down the quarter-mile track in bright sunshine and it seemed to me that they represented a modern version of the joust in almost every respect. The extravagant and ruthless specialisation reminded me of armour designed especially for the tournament; the ceremony and the curious rituals, some necessary and some simply a matter of style, cried out for commemoration.

At this time, I also discovered the first image which prompted my series of Astronaut painting. It showed Alan Shepard in his capsule in a group of four slightly blurred time-elapsed photographs, the blurring adding to the mysterious quality of his activities. I painted all four images in one painting, using black and silver paint, extending the time span of the image across the sequence of events depicted. I gave this painting to Robert Indiana, and painted a portrait of him as well, using the same system.

I began my series of ‘Starlets’, which are straightforward drawings of the human figure, with associated areas of flat colour which create volumetric ambiguities, ambiguities which I was later to exploit in abstract sculpture.

Both the Skydiver and Astronaut paintings showed the protagonist at different moments in the same picture, in the manner of certain early religious paintings. In the Skydiver paintings, the parachutist is shown both jumping from the air and later, landing on the ground. In the Astronaut painting the subject, Alan Shephard, is shown at four different moments during his journey into space, just as in a religious painting Jesus might be shown performing miracles, riding into Jerusalem, facing Pontius Pilate, being crucified and ascending into heaven.

There were frequent visitors to the loft on Coenties Slip, visitors who not only expressed an intelligent and enthusiastic interest in Bob’s paintings, but who also often bought them from him. The frequency of these visits seemed to increase as the summer wore on, until it became obvious that there existed a supportive audience for his art and for that of his contemporaries. I could not imagine an equivalent situation in London. The idea that people might come to your studio and buy things from you seemed impossible. In New York, it seemed that the artist actually had a recognised and useful role and need not be driven underground or to the perimeters of society to scratch a living as best he could by other means. This interested public encouraged American artists to take their work more seriously and to approach it in a more methodical and productive way. They seemed to have a truly professional role. I found this tremendously exciting; it was far more than I had ever allowed myself to expect, and it seemed enviable. The implicit note of apology or feelings of irrelevance which were typical of the artist in Britain at that time were not at all appropriate. America acknowledged the usefulness of artists, and seemed therefore to provide for them. The fact that they were producing a new art, one free from the cultural toils of the old world, was all to the good. Novelty was welcomed by the new people, who wished to subscribe to a new identity and a new system of values. The future seemed assured.

I could not afford to send my paintings back to London, so I left them in Bob’s studio.