Memoirs 1936–2011

Chapter 14 1963 Loose Ends

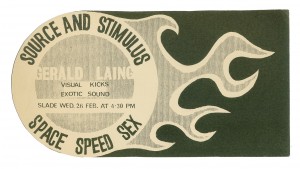

Source and Stimulus - Space, Speed, Sex

In late summer, London city streets are worn and dusty, awaiting the scouring wind and rain that autumn brings. Fournier Street, its handsome past subsumed by litter and peeling sun-baked paint, its colours all returned to dirty brown and its splendid doorways half hidden by confusion of commercial signs, was nevertheless welcoming and comfortable.

In my two months of absence it seemed to have mellowed and become more intimate.

The great size of American structures, of everything from domestic appliances to the landscape itself had rendered London almost a city in miniature, one that had a domestic scale even in its public buildings.

Golden sunlight shone across the patchwork quilt and bounced off the brass knobs of our iron bedstead that afternoon as we reunited with an enthusiasm heightened by long absence. I had been away for two months but the unfamiliar experiences to which I had been exposed made it seem even longer and it had changed me.

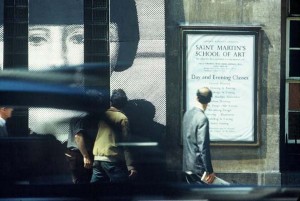

Though I had no sense of having achieved anything quantifiable by my journey, I returned to London with my confidence greatly increased. I still had little notion of what I might do at the end of this, my final year at art school; I simply got on with my work, which has always proved to be the best course of action to take. I painted constantly, in my studio room on Fournier Street in the evenings and at weekends, and during the day at St Martin’s, where I retired permanently to the top of the stair well, a cul-de-sac which was semi-private and in which I was left to my own devices. I met with no objections from the teaching staff, who were pleased that I had found my way and who were probably aware that in any case I would have brooked no interference. Some were actively supportive. With one of the painting teachers at St Martin’s, Alan Cooper (also, incidentally, a leading member of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, an anarchic jazz group which achieved some success) I put on an exhibition at the art school. It was entitled ‘Paintings of Photographs and Photographs of Paintings’. I provided the former and he completed the circle by providing the latter. Included in the exhibition was a photograph of me painting the photograph of Brigitte Bardot, which summed up the paradox.

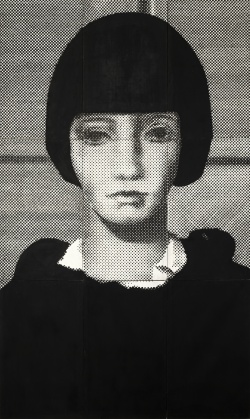

During the autumn term, I arranged an evening event which was entitled: ‘Source and Stimulus - Space, Speed, Sex’ at the Slade School of Art. I intended it to be similar in form to a cinema presentation; it began with a rough little 8mm film of my painting ‘Anna Karina’. It was made by my photographer friend, Joe O’Reilly, who had gone with us to Paris for the Biennale. He suffered from extreme nervousness and, while his chronically shaking hands had not prevented him from making wonderful still photographs in Paris, the panning shots in our film were like the hesitant wandering wobble a butterfly’s flight.

We took the big painting out onto Charing Cross Road, and showed it in various positions, standing against advertising hoardings, eclipsed by passing buses and reflected in shop windows in all the frantic activity of the city street. The film ended with animations of some alphabet and ‘speaking’ paintings I had done the year before -paintings of my own lips pronouncing letters or words in sequence which were intended to demonstrate the arbitrary, vague and inaccurate nature of interpersonal communication. The object of the film was to investigate the relationship between images used in art and in advertisement. The essential difference has to be one of intention and it is this unquantifiable quality which concerned me. It is the principle on which rests the whole practice of employing ‘found objects’ as works of art.

I am not convinced that by simply saying something is a work of art it becomes one. The process seems as arbitrary as ‘Simon Says’. However, it has been an accepted practice among many artists for almost a hundred years, ever since Marcel Duchamp chose his bottle rack and urinal and proclaimed them as sculpture. I cannot imagine that he would have been anything other than dismayed if he had realised that this essentially anarcho-satirical gesture was to become a habit, so to speak, and gather about it exactly the sort of established structure and bureaucratic hierarchy which he had intended to attack.

It was as an attempt to discover the difference (beyond that of intention) between my painting of Anna Karina, which had physical dimensions similar to that of an advertising hoarding, and an actual advertising hoarding on the street which caused me, with the help of some of my friends, to carry my work out onto the London streets and make the film.

The soundtrack consisted of pop music which, after the film had ended, was interrupted by a rather fruity voice murmuring “There will now be a short intermission” in the style then current in cinemas. At that point, spotlights picked out a girl dressed as an usherette and holding a tray on which there were pieces of bubblegum in cardboard holders. The holders were in the form of the smoking wheel from one of my dragster paintings, around which were painted the words “SPEED SPACE SEX”; a useful little summary of my current preoccupations. The wrapped gum was given free to the members of the audience, for although the girl holding the tray was meant to represent an ice cream seller, I knew that there was no chance that the audience would pay anything for her wares.

The second half of the performance consisted of a medley projected 35mm slides, some of which were of my paintings and the rest of source material or possible source material - dragsters, skydivers, astronauts and girls. The soundtrack consisted of recordings of dragsters at race meetings ( which were, incredibly, available on long playing records - just loud engine noises with a blurred background of Tannoy announcements); an American voice reading Kennedy’s speech on space exploration policy which was prompted by the early Russian successes with Sputnik and which ends so memorably with the words: “... by the end of this decade to the moon and return him safely back to earth”. (Children in Britain at that time were chanting ‘Catch a falling Sputnik, Put it in a matchbox, Send it to the USA’, in parody of a popular song entitled ‘Catch a Falling Star’); a particularly dramatic description of space rhapsody from an Arthur C Clark novel; and, for the girls, more music, with a special stress on the Crystals’ recording produced by Phil Spector and entitled ‘He’s a Rebel’.

I coordinated the images and music as best I could by adjusting the length of time for which each slide appeared on the screen, though sometimes I had to speed up or dawdle rather more than I wished.

The evening was a blend of what was later to be known as a Happening and a performance. I do not think that anything like it had been done before. In it, I was attempting to create a complete and exclusive world for my art; exclusive, that is, of anything which was irrelevant to my vision.

This desire is not uncommon; to find the perfect environment for a work, to remove jarring and competitive objects even the selection of an appropriate frame for a painting, all of these eminently understandable objectives are part of a similar endeavour.

Like any language, art can easily be misunderstood. Systems of communication are imperfect even between people who share similar backgrounds, beliefs and experiences; small wonder that an individual and obsessively developed vision may be obscure to the outside observer. Later in the 1960’s abstract and minimal sculpture was to become so obtuse as virtually to disappear unless it was presented in a sympathetic or supportive environment - in other words, in order to be detected as art it had to be seen in an art gallery.

However hard he may try to sustain a perfect place and a perfect comprehension for his work, an artist will always and repeatedly be brought up short by the rough corners of reality, which inevitably include a good dose of misunderstanding.

My hubris was deflated almost immediately. I had naturally been quite pleased when one day a photographer appeared at St Martin’s and asked to photograph me with ‘Anna Karina’ for a magazine. Soon after the ICA event, the photograph appeared, on the curiosity page of an obscure Dutch magazine called ‘ZONTAGS FRIEND’, with the believe-it-or not caption ‘PORTRETTEN IN PUNTJES’ (pictures in dots). I was shown next to a Yorkshire terrier named Brandy who smoked filter cigarettes (‘ROKENDE HOND’). So much, I thought bitterly, for my universal contemporary icons.

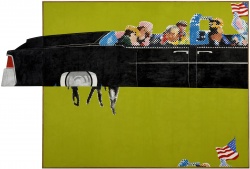

That November, the shiny image of America cracked from side to side. I heard the news in my studio on Fournier Street, when radio broadcasts were interrupted to announce the ghastly events in Dallas. I detested the treacly talk of Camelot in Washington, and paid little attention to American politics. In spite of the ghastly violence of the twentieth century we had been endowed with a sanitised version of the past, which produced in us a sense of stability which was as deeply held as it was false. Thus, when the president of the richest and most powerful country in the world proved to be vulnerable to the assassin’s bullet, it came as a terrible and fundamental shock, which forced us all to adopt more realistic attitudes towards the world about us. It drove from us our comfortable and wilful naiveté. Henceforward we became less easy to please and to convince, and much harder to placate. This murder fatally eroded the power of authority and opened the door to chaos.

It left us to our own devices.