Catalogue Raisonné. Lincoln Convertible, CR030

Search the Catalogue

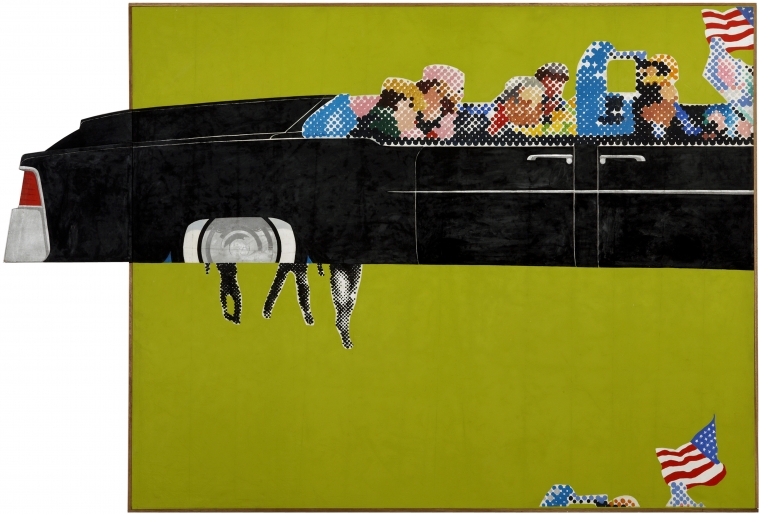

Lincoln Convertible

CR 030

London

1964

Oil on irregular, shaped canvas

111 x 73 inches

Citations and Comments

That November the shiny image of America cracked from side to side. I heard the news in my studio on Fournier Street, when radio broadcasts were interrupted to announce the events in Dallas. I detested the treacly talk of ‘Camelot’ in Washington, and paid little attention to American politics. In spite of the ghastly violence of the twentieth century we had been endowed with a sanitised version of the past, which produced in us a sense of stability which was as deeply held as it was false. Thus, when the president of the richest and most powerful country in the world proved to be vulnerable to the assassin’s bullet, it came as a terrible and fundamental shock, which forced us all to adopt more realistic attitudes towards the world about us. It drove from us our comfortable and wilful naiveté. Henceforward we became less easy to please and to convince, and much harder to placate. This murder fatally eroded the power of authority, and opened the door to chaos.

It left us to our own devices.

Images from the Zapruder home movie of the assassination of JFK were published in Life magazine soon after the event. These became the source for my painting, which shows parts of two sequential frames.

The division between these two frames is the straight line along the bottom of the car, the Lincoln Continental, a superior – and enormous – convertible. To call attention to this I extended the tail of the car beyond the edge of the frame on a shaped canvas. For some reason I also felt bound to paint coloured dots to commemorate the tragedy, the only time that I have ever done so. I usually paint black dots.

I intended to convey a Buddhist meaning, where colour rather than black is associated with mourning. It also enabled me to clarify two important visual features of the drama – Jackie Kennedy; pink suit and pill-box hat, and the yellow roses held by Governor Connolly of Texas.

The lower frame is the earlier one. You can see by the relative positions of the flag that in the upper frame the car has moved forward slightly. Below the edge of the upper frame the legs of the Secret Service men running towards the car are visible.

In the car the President has already been hit and has slumped forward. Jackie is leaning over him solicitously. Later she was to panic and climb onto the great flat trunk of the car. Just in front of the President and his wife is Governor Connolly holding his yellow roses. He, too, has been hit but this is not yet evident. In front of and beside him are the bodyguards and the driver.

I shipped the painting to New York in 1964 along with the other paintings I had ready for my first exhibition at the Richard Feigen Gallery. Richard would not exhibit it, as he considered the subject matter to be too traumatic. Too much of a downer, as we said then. Eventually I took it off its stretcher and it then spent twenty years folded up in a garden shed in New Jersey, from which I recovered it in about 1995 and re-stretched it. This accounts for its condition, which I think of as an important part of the painting’s presence and history.

As far as can be ascertained, this is the only painting of the assassination of President Kennedy made at the time of the event itself.

I painted Lincoln Convertible in London immediately after the Kennedy assassination. I had spent the previous summer in New York and the shock of the events contrasted violently with the optimistic and enthusiastic emergent art scene there, to which I had been introduced by the then-known Warhol, Rosenquist, Lichtenstein and Indiana.

The source for the painting was two frames from the amateur 8mm Zapruder film of the event. These were first published in the French version of Life magazine, a copy of which somehow fell into my hands.

Soon after the painting was finished, Richard Feigen, who was to be my dealer throughout the 1960s, visited my studio at Fournier Street in Whitechapel in order to invite me to come to live in New York and show in his galleries in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

This I did for the subsequent six years. He arranged to ship all of my work to the USA, but when Lincoln Convertible was delivered he felt that the subject matter of the painting was too raw and difficult for his clients (the whole of America was traumatised by the event) and so I took the canvas off the stretcher and stored it, rolled up, in a garden shed in my father-in-law’s house in New Jersey for the next 25 years.

When David Mellor was selecting works for his exhibition The Sixties Art Scene in London at the Barbican in 1993. I told him about the painting and showed him a slide of it. He was very keen to include it in his exhibition and though it was too late to include it in the catalogue, which had already gone to print. I retrieved it from New Jersey and took it to my studio in Scotland, and made a new stretcher for it. It had suffered in storage so I felt it necessary to repaint the green and black areas and remake the tail of the car.

The painting is a genuine and timely document of a dreadful moment in US history and as far as I know the only painting actually made at the time.

Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 shook the world, not least because scenes of the assassination

were quickly disseminated worldwide by the media. For many it has become a defining moment in television history. Interestingly, the images so familiar today and used by Gerald Laing in Lincoln Convertible came from an amateur movie by Abraham Zapruder, as the press were not covering the presidential cavalcade in Dealey Plaza. This colour film was to become crucial evidence for the Dallas police, while the other copy was sold to Life magazine, who then published stills from the footage. Laing wrote an account of the day: That November the shiny image of America crocked from side to side. I heard the news in my studio on Fournier Street, when radio broadcasts were interrupted to announce the events in Dallas. I detested the treacly talk of ‘Camelot’ in Washington, and paid little attention to American politics. In spite of the ghostly violence of the twentieth century we had been endowed with a sanitised version

of the post, which produced in us a sense of stability, which was as deeply held as it was false. Thus, when the president of the richest and most powerful country in the world proved to be vulnerable to the assassin’s bullet, it come as a terrible and fundamental shock, which forced us all to adopt more realistic attitudes towards the world about us.*

Instead of using a single frame from the stills illustrated in Life magazine, Laing included the lower half of the frame below as well, which places

the main image in a cinematic narrative. He used a series of painted dots to create a sense of form modelled with light and shade, borrowing the technique from commercial printing processes, particularly posters in the underground. He usually used black dots but here chose colour as he “intended to convey a Buddhist meaning where colour rather than black is associated with mourning. It also enables me to clarify two important visual features of the drama - Jackie Kennedy, with pink suit and pill-box hat, and the yellow roses held by Governor Connolly of Texas”.**

The size and shape of Laing’s Lincoln Convertible were inspired by the size of the Lincoln Continental convertible itself. The extended canvas emphasised the division between the two frames, but also created a sense of forward movement os the front of the vehicle disappears from view beyond the canvas.

*Laing, Gerald, extract from unpublished ‘An Autobiography’, emailed to author 22 February 2006.

**Laing, Gerald, extract from unpublished ‘An Autobiography’, emailed to author 22 February 2006

- Young Contemporaries 1964, RBA Galleries, London, 1964

- Gerald Laing, Keith Lingard, David Milne, Saint Martin’s School of Art, London, 1964

- The New Generation, 1964, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 1964

- Gerald Laing: A Retrospective 1963–1993, The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, 1993

- Pop 60s: Travessia Transatlântica/Transatlantic Crossing, Centro Cultural de Belém, Lisbon

- Gerald Laing: From 1963 to the Present, Bourne Fine Art, Edinburgh, 2004

- Gerald Laing: Iraq War Paintings, Spike Gallery, New York, 2005

- British Pop, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, 2005–6

- Space, Speed, Sex: Works from the early 1960s by Gerald Laing, Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, London, 2006

- Pop Art! 1956–1968, Scuderia del Quirinale, Rome, 2007–8

- When Britain Went Pop. British Pop Art: The Early Years, Christie’s King Street, London, 2013

- Gerald Laing 1936–2011: A Retrospective, The Fine Art Society, London, 2016

- This Was Tomorrow: Pop Art in Great Britain, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2016

- Source and Stimulus: Polke, Lichtenstein, Laing, Lévy Gorvy, London, 2018

- Lincoln Convertible