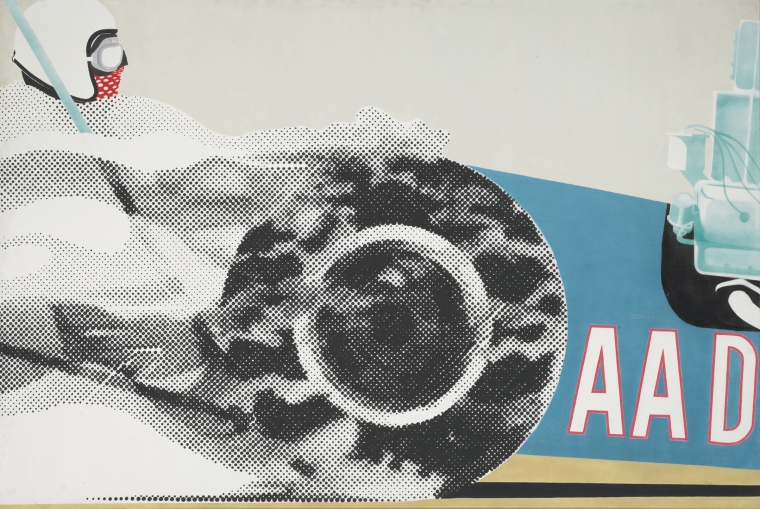

Catalogue Raisonné. AA D

Search the Catalogue

AA D

Catalogue No. 38

Artist's CR 036

1964

London

Oil and cellulose paint on canvas

55 x 83 inches / 140 x 211 cm

Collection: Private collection

- (Richard Feigen Gallery, New York)

- Collection of John and Kimiko Powers

- Collection of Academy for Educational Development, Washington D.C.

- Sold at auction by Shannon’s, Woodmount Road, Milford, Connecticut, 28 April 2011, Lot 209

- Private collection

- Sold at auction by Christie’s King Street, 23 May 2012, Lot 18

- Private collection

- First Jump Course (One Man Show), Richard Feigen Gallery, New York, NY, 1964

- New Images, Richard Feigen Gallery, New York, NY, 1964

- Space, Speed, Sex: Works from the early 1960s by Gerald Laing, Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, London, 2006

- Mario Amaya, Pop as Art: A Survey of the New Super Realism, Studio Vista, London, 1965

- Gerald Laing, 'Aspen Notebook', unpublished manuscript, 1966

- Space, Speed, Sex: Works from the early 1960s by Gerald Laing, exhibition catalogue, Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, 2006

- 20th Century British & Irish Art Evening Sale, 23 May 2012, sale catalogue, Christie's King Street, London, 2012

AA D is an example of the very formal figurative painting with which I was involved in 1962–5. At that time I was very concerned with conveying a simple idea in the least ambiguous manner possible. A figurative style was the easiest starting point and at the same time acted as a justification for beginning the painting and for the later formal deviations I made. However, I was never concerned with an atmospheric type of space in the painting - I was always intent on the idea of the tactile surface and the painting as an object. My earliest paintings of this group involved only half-tone black and white - but at the time of AA D I had introduced colour as well and was interested in the interplay between the half-tone modelled areas and the colour, which had the possibility of being read either as surface or in dramatic depth. I found it essential to make a strong linear boundary between the coloured and modelled areas, often the sort of boundary that is used in heraldry. Naturally there were subjects which lent themselves more to this than others, both for formal and psychological reasons. A painter whose work has always excited me is Paolo Uccello, whose flat formal depiction yet strong concern with objective fact influenced my work very strongly.

AA D is a painting of a drag racing car, and while the rather naive comparison can be made between the drag racer and the mounted knight, it is more pertinent to note that the compositional possibilities are similar. Organic anonymity coupled with mechanical identity are common to both, and assisted me in my endeavour to establish an authoritative tactile image which worked towards that inevitability that heraldic images, governed as they are by strict rules, always have.

The sociological implications of the drag racer, to me as an Englishman at least, are very interesting. AA D was painted in London, at a time when most of my contemporaries were entranced by a Utopian dream of an America they have never visited but which we all envisaged, with Hollywood’s help, as a classless (boon to the English) bright society, full of an optimistic naivety which made all things possible and which was typified by the gleaming exotic and extravagant playthings which were heavily propagandised in Europe. Of these, drag racing was the wildest.

Perhaps I should make some note of the technicalities involved in making these paintings. Apart from the strict geometric division between half-tone and coloured areas, the black dots which comprised the half-tone areas were themselves modulated to the total proportion of the image, canvas, etc., their average size being controlled by a ruled grid prepared on the canvas beforehand. Individual size was governed by the requirement of tonal intensity; thus the process became a matter of tonal drawing, or ‘tonal pointillism’.

'Aspen Notebook', Gerald Laing, unpublished manuscript, 1966

Racing cars, dangerous-sport daredevils, astronauts, film stars and starlets - all the unapologetic obsessions of an extroverted young man at the height of the swinging sixties - were the preserve of Gerald Laing’s paintings and screenprints at the height of his Pop phase between 1963 and 1966. Born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, he had first visited New York in summer 1963, while still studying at St Martin’s School of Art in London, and during that stay had worked briefly as an assistant to the American Pop artist Robert Indiana. ‘It was during that summer in New York,’ he recalled in 2005, ‘that I first identified the four major themes which were to preoccupy me for the next three years: Dragsters, Skydivers, Astronauts and Starlets.’ On his graduation in 1964 he moved immediately to New York, which he made his base for the next five years and where he became an integral part of the city’s thriving art world.

Laing’s Pop paintings, of which AA D (Racing Car) is a characteristically bold and streamlined example, proposed a personal dialogue with the mechanistic procedures explored by two of the movement’s greatest American exponents, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Like Warhol, he took much of his imagery from mass-media photographic sources and conveyed it with a deadpan neutrality of technique; unlike Warhol, however, who had the found images transferred photographically to silkscreens and then printed onto his canvases, Laing duplicated his sources entirely by hand, interpreting them according to his own rigorous formal standards. The procedure he adopted was closer to that of Lichtenstein’s emulation of the ‘Ben-Day’ dots used for the printing of comic strips, though again with Laing’s own twist: his own dots, mimicking the newsprint screens of half-tone photographic reproduction, were applied singly with the tip of his fine brushes rather than through the perforated stencils favoured by Lichtenstein. While appearing to reject the entire tradition of belle peinture and expressive brushwork, Laing explored the potential of subtle variations of mark and tone through the pressure of his brushes and the shape and size of his circular touches.

Every major Pop artist understood well the necessity for developing a personal iconography and set of procedures with which to distinguish his or her work from that of the other artists working on both sides of the Atlantic within a similar aesthetic, and from the same pool of publicly available imagery. For Laing drag racing (a thrill-seeking sport created in the USA in 1955) proved to be a powerful expression of his masculine identity and enthusiasms, expressive of the speed and dynamism of modern life - as cars had been for the Italian Futurists half a century earlier - and of the exuberant risk-taking practiced by others, including rock stars, during that vibrant decade. The painting’s title, emblazed in capital letters on the side of the car, almost certainly derives from the recently introduced AA/Fuel Dragsters that were to break the 200 mph barrier in 1965. The fact that these racing cars were themselves decoratively embellished added to their attraction as subjects, though Laing astutely concentrates as much on such intangible, almost unrepresentable, matters as the clouds of dust thrown up by the spinning wheels as by the cars’ bodies themselves. Like the masked and helmeted driver who preserves his anonymity in the cockpit while projecting a sense of his unassailable courage and recklessness, the impenetrable surface of the car itself becomes camouflaged by its own movement. In the process of being painted, the car and its driver become both emblem and mirage, a freeform fantasy of life in the fast lane.

20th Century British & Irish Art Evening Sale, 23 May 2012, Marco Livingstone, sale catalogue, Christie's King Street, London, 2012, lot 18

- AAD